(Image credit: Tsering Topgyal/Associated Press)

WARNING: long read…

While I was surprised by the small but vocal backlash, against India’s Daughter, I was even more amazed to see the amount of time and energy people have spent writing blogs, tweeting, posting, gathering and sharing global rape statistics (someone has even made a YouTube documentary called “United Kingdom’s Daughter”). All this to discredit a documentary that does more than any other I have seen to honour the memory of an amazing woman who lost her life in a brutal gang rape in India.

The thing that saddens me most is that, if even half these people spent half of the same energy to actually start a discussion on the gender inequality issues we have in India (like every other country), just imagine the progress we could have already made.

To begin with, I don’t know how anyone who has seen this documentary can say that it is an indictment of Indian society and ALL Indian men. While I saw some of our imperfections (as with EVERY society on the planet), I also saw the story of a beautiful, modern, smart, independent young woman with forward thinking and open-minded parents. It made me want to strive to create a society where Nirbhaya’s are the rule, and not the exception. Why not put every last bit of energy we have towards making India a country where “a girl can do anything”, as Nirbhaya used to say.

Nobody in the world, or in their right mind, believes that rape, sexual abuse, misogyny and sexism are a uniquely Indian problem. Some of the outraged point to a Western media bias against India, saying the media only focuses on negative stories about India. To them I say, yes, there absolutely is a bias in Western media, but surely you do not believe that this documentary is part of some greater conspiracy to malign India, because the facts within it remain undisputed. The brutal rape happened, Nirbhaya’s parents have suffered, all India was outraged and our judiciary and government took unprecedented action as a result of it, and the attitudes of some men (not ALL Indian men) exist in society.

Also, when did the Western media become our moral compass for how we see ourselves? I for one do not care what the Western media has to say about India; we are defined by our own actions. Let us never forget that. What I am saying is that even if the film was biased, why not take the parts that are real and work to fix them. A great nation does not fear criticism or cower when faced with unsavory truths, but shows the world a better way and leads from the front. I want India to respond by demonstrating how we will take the lead on the gender equality movement, and in doing so show the rest of the world a better way forward. That is the best %#&@ you…

One final thought on this; it is easy to be critical of everyone and everything. Criticism comes very easy to all of us, and it also makes for more pithy tweets, Facebook posts and attention grabbing headlines. But in the end, criticism alone neither fosters meaningful dialogue nor facilitates the type of debate than can lead to change. In this storm of criticism, consider that the most important aspect, Nirbhaya, has become a footnote.

So we can choose to stay focused on being critical of every little detail, event and person, ignoring that there is no such thing as perfection and that we are all imperfect. Or we can accept that change does not come about in a logical fashion, on some pre-ordained schedule or through luck and prayer. Instead, we can recognise that serendipity most often arises out of all the imperfection, horror and chaos around us. If we can seize on these opportunities and use them to further causes (for the greater good, rather than for ourselves) then we have a much better chance of achieving success and creating lasting change.

Now let’s examine the so-called ‘facts’ and the various arguments that people have been throwing around in social media to discredit the film and film maker.

1. Shocking as it may be to see and hear in full technicolour, nothing the rapist or his lawyers say are things we have not heard from our own leaders from across the gender, political and social spectrum. Read: “Why India’s Daughter Holds A Mirror to Our Society” (each quote has a link to a reputable media source). I think we can also agree that the rapist and his lawyers were not provided a script and were all allowed to speak their minds. As an aside, I also appreciate the fact that the documentary had no narration; which one can argue might have given it an inherent bias.

2. Leslee Udwin has stated many times and even sworn in an interview with Scroll.in, on her children’s life, that she did not pay a single penny to the rapist or his lawyers to gain the interviews. One other point to consider is that is entirely plausible that Mukesh Singh was prepped by his lawyers and encouraged to speak in order to help his plea hearing. It might explain why he kept insisting that he was always behind the wheel and never touched Nirbhaya.

3. There has been much flap about why Nirbhaya’s friend, who was with her on the bus, did not appear in the film. Any psychologist will tell you that a person who has suffered the level of physical and emotional trauma he did will likely take dozens of years before they are able to talk about it; leave alone publicly. This is a well-documented fact. Second, Ms. Udwin has said that she tried for six months to get him on film but that he refused. More recently Ms. Udwin told the Asian Age that he asked for money and she refused on moral grounds. (Source: Asian Age article).

4. Ms. Udwin clarifies in another interview that Nirbhaya’s father did not want to use his daughter’s real name in the Indian version but agreed to feature it in the International one. However, with the Indian government banning the film, neither she nor the BBC has had much control over which version is being posted across the internet. However, I do think people are rightly upset with the narrow and ‘sensational’ manner in which the BBC chose to market it, and for removing global rape statistics at the end of the film. Ms. Udwin says this was done without her permission and she too is unhappy about it.

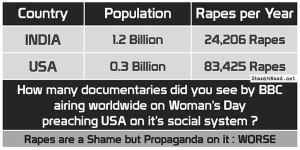

5. I have seen the graphic below posted in many places to prove that there are more rapes in the developed world than in India.

Again, nobody has claimed that rape is solely an Indian problem but let’s review these statistics, with some additional context, and by digging a little deeper into some of the unique underlying societal issues:

- Marital rape is still considered legal in India (unlike in the USA and UK)

- Until very recently, an 18th century, ‘two-finger’ test was still being used on rape victims in India. There are still questions on whether this recent ban has been fully implemented (Firstpost article).

- Further, until the outcry after what happened to Nirbhaya there was little rape sensitivity training within the police force that I am aware of. Personally, I know in many cities I still think twice about involving the police in ANY matter. Ask yourself how comfortable a woman might feel going to a police station in Haryana to report being raped?

- Consider what we subject rape victims to during the legal process and how they are repeatedly humiliated in open court, as happened with both Suzette Jordan (Scroll.in article) and the Uber rape victim.

- It is true that across the world, rape is the most underreported crime, but if we are honest with ourselves, can we deny that in India there are perhaps greater societal and familial pressures NOT to report incidents – for fear of “shaming” the family? Globally, and in India, some 90%+ of rapes are committed by someone known to the rape victim.

The point is that there are still many barriers and disincentives in the Indian systems and society that we need to work on changing.

- The practice of dowry is still prevalent practice, and nobody can deny that in many parts of India, girls continue to be seen as financial burdens while boys are considered prized possessions. But don’t take my word for it:

- Look at gender gap figures from a 2013 World Economic Forum study where we “emerged at the near-bottom of the heap, before only Azerbaijan” (Source: Times of India).

- Or at the female foeticide figures; a panel of Indian experts, gathered at CII earlier this year, described it as “Though, a lot of laws and acts have been framed against this evil, until and unless mind sets see a revolution, the gender ratio will keep falling” (Source: Times of India)

- Look at a 2014 study of attitudes among youth conducted across 11 major cities in India which found that the importance of “gender equality” scored the lowest. Here are a few other findings (Source: Firstpost article):

- “52% of Young India thinks a woman’s place is in the kitchen”

- “39% of girls and 43% of boys, agreed that women have no choice but to accept a certain degree of violence”

- “55% women and 59% men, whether a woman wears jeans or a sari, her clothing is to blame if a man chooses to manhandle her”

- “A whopping 43% of the men are under the impression that well, tough luck women, you had that coming, now suck it up and accept it (on sexual violence)”

6. Some feminists have also been critical of the film for ignoring their movement in India. First, this film was never meant to document the rise of feminism in India, or showcase the movement. I laud all the women in India who have dedicated their lives and been championing gender equality. Many have been shouting till they are hoarse from the rooftops for decades – and now suddenly a British woman has appeared out of nowhere and grabbed all the headlines, perhaps positioning herself as the champion of this cause. While, I fully understand where the emotions are coming from (and they are justified), I also ask if the issue is not bigger than any one individual or movement. In the end, does it matter if the spark was lit by a white woman or a green Martian? Why not use it as an opportunity to now take control of the debate and further this cause by driving the public discussion. Let’s use it to keep the media spotlight on the issue and affect much needed change in our society.

7. The title has been another bone of contention because some say it serves to reinforce the patriarchal mindset that exists in society. On the title, even if one concedes this as a valid point, does it really matter? Living in America with political correctness now reaching a point where such great care is taken not use even a vaguely incorrect or offensive term – I feel like the focus on the actual issues and debate is more often than not diluted. This undue sensitivity and hang-up with words or terminology might make us feel better, but it also serves to ensure that we miss the forest for the trees.

8. There has also been much ink spilled over Ms. Udwin allegedly flouting and disrespecting Indian laws, both during the approval process and with the film’s release. Yet, the government, in all their rhetoric, so far has been unable to make its case in a way that separates the legal and procedural aspects from the content of the documentary. If it turns out that Ms. Udwin broke laws, then absolutely prosecute her, BUT it still does not change the realities contained on film. It seems to me that the government is more ashamed of the picture it paints of India and the negative impact it might have on India’s image abroad; rather than any serious legal lapses. They have gone as far as calling it a crime that Ms. Udwin released the film – I ask them; would it not be a greater crime NOT to release this film, sweeping these realities under the carpet and never giving us an opportunity to change them?